Did you know you can use ground penetrating radar in paleontology? While it’s not a super common use for GPR, many paleontologists are hopeful about the potential of ground penetrating radar in paleontology.

We had the opportunity to put GPR scanning to the test on a very large construction site in Southern California when fossilized whale bones were discovered during the excavation process. Here’s what we learned on this whale of a project (yes, we said it!).

Who Knew? Ground Penetrating Radar in Paleontology

Traditional fossil-finding is a pretty low-tech endeavor. Aside from GPS, it’s all about manually digging and looking for anomalies in the soil. This process is effective but time-consuming, and when you need to excavate a site quickly, a manual approach can be very inefficient.

This has led experts to look for more efficient methods, like using ground penetrating radar in paleontology. It’s a pretty novel application, meaning that GPR scanning in paleontology is still relatively rare.

Why? Primarily because fossil bones tend to have a very similar density to rocks, making it difficult to distinguish rock from bone. Plus, fossils are generally small, and since GPR can’t produce tons of resolution, it’s easy to get false negatives.

Still, there have been many successful applications of ground penetrating radar in paleontology, like the detection of sirenian (aka sea cow) fossil bones in a sunflower field in Tuscany. So, we knew it was possible.

The Project Details: A Paleontologically Significant Discovery

So why did the construction team care about whale fossils in the first place? Well, there’s a California State Law called the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) that requires an observer to be on site for construction projects to keep an eye out for discoveries that are archaeologically or paleontologically significant. And that’s exactly what happened here.

We got called into a billion-dollar construction site in Southern California after their archeological observer identified some whale bones. The owner called in a paleontology firm, and the paleontology firm called us.

The fascinating part is that this site was located several miles inland – but 5 million years ago, it would have been deep enough in the ocean for a whale to swim around comfortably. The paleontology firm was familiar with GPR and its potential capabilities, but they hadn’t actually put it to the test before.

They wanted to give it a try on this project, so they brought us out.

We were in luck because the soil on site was ideal for locating fossils, which isn’t always the case. You see, GPR looks at electromagnetic differences in elements by relying on contrast, such as the difference between organic material like soil and inorganic material like a steel pipe.

Normally, looking for a rock or fossil in dirt is a tough ask.

But since the in situ soils on this particular site were very homogenous and clean (no rocks or water, etc.), GPR had a chance at finding very small differences – like fossilized whale bone.

Plus, this site was inland, and when the dirt is dry and isn’t salty, it’s perfect for GPR data reading because the EM pulse will propagate very well.

Long story short, the site in question was a great candidate for GPR because:

- The soils were homogenous and clean

- We were looking for iron-based fossils (so there would be contrast)

- The soils were sandy (not wet or salty)

- The fossils were relatively shallow

On Discovering a Whale Underground

Unlike many of our normal GPR processes, there was no live interpreting on the site for this project. With a large surface area to cover, it’s easier to scan everything first and then look at the data from the office afterward. For this project, we used Geolitix software to save and post-process the data, which proved extremely useful.

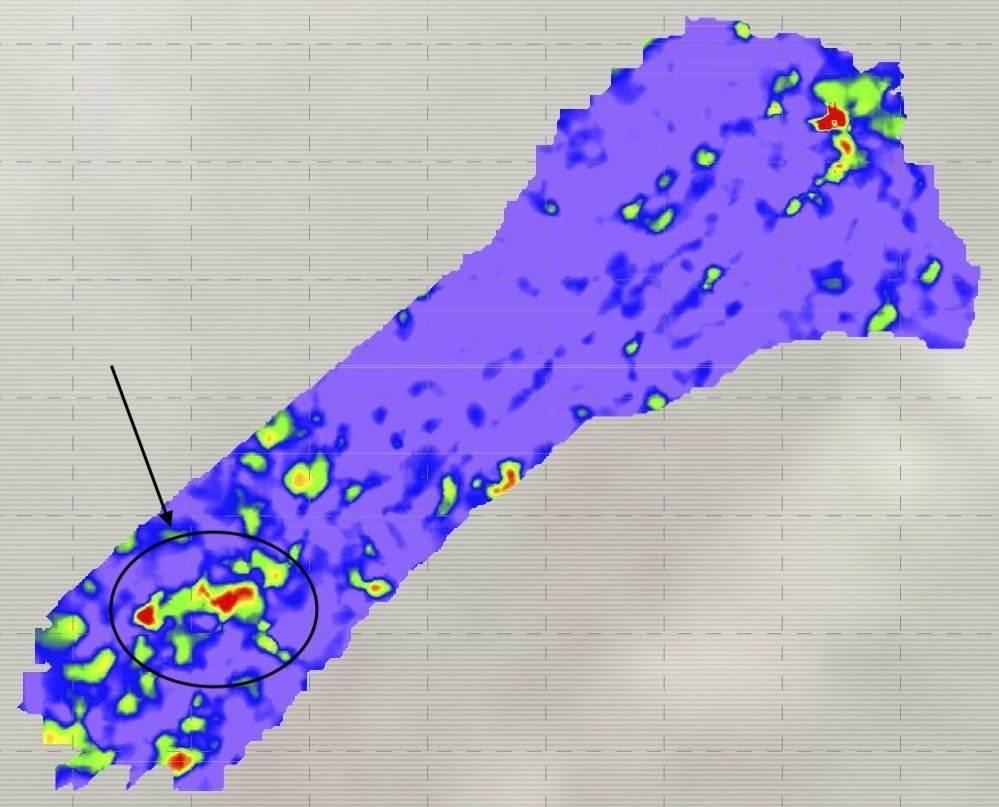

Geolitix enabled us to discover anomalies in a few areas.

We found one set of anomalies that was about sixty feet away from their active dig site. It was a whole cluster of bright anomalies (see circled area on image) that were fairly consistent through various depths of soil. We handed this finding over to the paleontologist, who agreed that this particular area warranted further investigation.

They went out to the spot, started digging, and found heavily stained soil.

Let’s back up for a second. Here’s a quick primer on fossils: Fossilization is essentially the replacement of organic with inorganic material – it’s the mineralization of organic materials. For example, many fossils are mineralized with iron. However, mineralization can occur with various minerals, including Fool’s Gold (which looks really cool, by the way).

So, when they found the stained soil, the paleontology team realized that the fossils were literally rusting! After digging into the spot, everything was stained, but there were no physical fossils left. Since the fossils there were relatively small, they concluded that they had probably completely oxidized – literally rusted away.

Unfortunately, there wasn’t anything to retrieve in that spot, but it proved that ground penetrating radar in paleontology would be effective in these conditions. In fact, they’ve found fossils in two locations on that site so far!

They believe they’re from the same whale, but they can’t be sure. We don’t know what type of whale yet, but we do know it was a big one, and it’s estimated to be around 5 million years old! Pretty crazy, right?

On Underground Scanning for Fossils: The Potential for Ground Penetrating Radar in Paleontology

This project is still ongoing, and they might come across more fossils as they continue to excavate. We’re ready to lend a hand to scan other areas if needed as the project continues.

This was a thrilling job for us because we got to test the potential for ground penetrating radar in paleontology. It’s not every day that you get to be part of an actual paleontology dig.

While it’s not always foolproof, thanks to the mineralization of fossils, GPR can be a great way to save some time during the excavation process. In the right conditions, it’s a useful method for locating anomalies and giving paleontologists a better idea of where to dig.

If you need help locating fossils (or anything else) underground at your excavation site, contact us today.